Humphrey Bogart — some of his greatest films

Social-Media-Optionen

Table of contents

- Stand-In (1937)

- The Roaring Twenties (1939)

- The Maltese Falcon (1941)

- Casablanca (1942)

- To Have and Have Not (1944)

- The Big Sleep (1946)

- Dead Reckoning (1947)

- Dark Passage (1947)

- Key Largo (1948)

- The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948)

- Knock on Any Door (1949)

- Tokyo Joe (1949)

- In a Lonely Place (1950)

- The Enforcer (1951)

- Sirocco (1951)

- The African Queen (1951)

- Deadline – U.S.A. (1952)

- Beat the Devil (1953)

- The Caine Mutiny (1954)

- Sabrina (1954)

- The Barefoot Contessa (1954)

- We’re No Angels (1955)

- The Left Hand of God (1955)

- The Desperate Hours (1955)

- The Harder They Fall (1956)

-

Stand-In (1937)

Bildquelle: United Artists, Filmverlag Fernsehjuwelen

When Humphrey Bogart—today the unforgettable titan of classic Hollywood cinema—was still subscribed to supporting roles in the same era of the studio system, he played the production manager of a Hollywood studio.

„But don’t forget that in Hollywood you also turn the other cheek,“ says Douglas Quintain to a New York banker (Leslie Howard), who now wants to turn the ruinous Colossal Pictures into a highly profitable company, but—unlike his mentor Quintain—has not the slightest idea of the mechanisms of the Californian dream factory.

-

The Roaring Twenties (1939)

Black-and-white scene with Humphrey Bogart and James Cagney as prohibition gangsters in suits and hats in a dark alcove, Bogart’s character carries a revolver.

Bildquelle: Warner Bros. Pictures

The World War II veteran who becomes a successful prohibition gangster after returning to the US from the Western Front and, in all his ruthlessness, seeks the deaths of his two comrades-in-arms—this George Hally is exemplary of Bogart’s supporting career in the 1930s, when he was initially billed behind big stars like James Cagney before emerging from the sea of mediocrity during the Second World War.

-

The Maltese Falcon (1941)

Bildquelle: Turner Entertainment, Warner Bros.

Bogart’s Sam Spade in „The Maltese Falcon“ is something like the archetype of the noir protagonist, the cynical, hard-boiled but principled private detective who becomes entangled in an amoral web of murder, deceit and greed under false pretences.

With this iconic portrayal, Bogart not only made himself immortal, but also characterised the Hollywood private detective who uncovers a crime complex with subtle sophistication, alert instinct and, of course, a slight toughness—not without suffering psychological damage himself in the process.

-

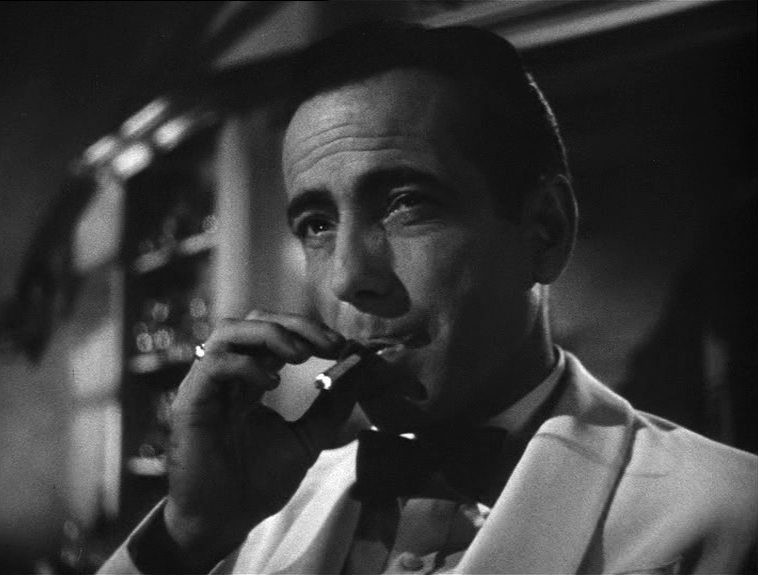

Casablanca (1942)

Bildquelle: Turner Entertainment, Warner Bros. Pictures

Rick Blaine, the American bar owner in the Moroccan metropolis of Casablanca, who is drowning in heartbreak when Ilsa Lund (Ingrid Bergman) enters his bar amidst the noise of the impending Nazi occupation, an agonising reunion after a year.

With „The Maltese Falcon“ Bogart was instrumental in the birth of a film classic—and a second time shortly afterwards with „Casablanca“. Like the detective Sam Spade, the nightclub owner Rick Blaine was also a typical Bogart character—a guy, beaten by fate, who knew how to impress in an explosive environment with his almost outrageous composure.

In „Casablanca“, Bogart spoke lines that became catchphrases—“Here’s looking at you, kid“, „We’ll always have Paris“ or: „I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship“. And Bogart transformed the cigarette into a fifth limb like perhaps only Michel Piccoli did.

-

To Have and Have Not (1944)

Bildquelle: Turner Entertainment, Warner Bros. Pictures

Steve and Slim, the nicknames of Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall’s characters in „To Have and Have Not“, became synonymous with a romantic coolness that had never been seen on screen before. The way in which Bacall, the unknown newcomer, and Bogart, the old screen star, exchanged glances, communicated with cigarettes and drinks, was the invisible Eros par excellence—and behind the scenes the beginning of one of Hollywood’s greatest love stories.

Bogart plays the soldier of fortune Harry Morgan, who, with his faithful companion Eddie (Walter Brennan) and his small boat, is sent to rescue a French resistance leader from the French colony of Martinique in the middle of the Second World War—one of Bogart’s roles in which a soft core is revealed in the tough guy under the influence of the morally right decision.

-

The Big Sleep (1946)

Bildquelle: Turner Entertainment, Warner Bros.

With Philip Marlowe, written by Raymond Chandler, Bogart played the second of perhaps the most famous hardboiled detectives in film history after Sam Spade in „The Maltese Falcon“.

In the manner of the smart lone fighter who sees through and anticipates (almost) everything, Bogart chases after the truth in a perfect noir pose behind a dense web of lies in order to cover up the missteps of two daughters from a wealthy family.

His Marlowe is human, if only because of his peculiarity of constantly tugging at his earlobe while thinking. The film, the role: all this seems to be Humphrey Bogart’s natural Hollywood habitat.

The story, which revolves around a family problem that Marlowe is supposed to solve for an ailing patriarch with the utmost discretion, not only confuses audiences to this day, but was also hardly understood by anyone on set and plays no role in the film—because ultimately „The Big Sleep“ served solely to exploit the thrill of the new on-screen couple Bogart–Bacall, who finally became a real couple during filming.

-

Dead Reckoning (1947)

Bildquelle: Columbia Pictures

For the film noir „Dead Reckoning“, Columbia borrowed the secret king of Noir Humphrey Bogart from Warner Bros.—he plays Captain Rip Murdock, a returning war veteran who wants to solve the disappearance of his comrade and friend Johnny Drake (William Prince) and—in typical noir style, very much in the spirit of Bogart—becomes embroiled in a dark affair.

Bogart/Murdock narrates the main plot as a flashback from off-screen. He tricks them all, the only weak point being his tendency towards romance, which (almost) brings him down. Officer Murdock is a hard-boiled character, almost like one of Bogart’s private detectives with their nihilistic nonchalance that allows them to wade through any puddle of society, no matter how murky. But Bogart plays him so freshly here that you can hardly get enough of him.

-

Dark Passage (1947)

Bildquelle: Turner Entertainment, Warner Bros.

In the first part of “Dark Passage” one only hears his voice, but never sees his face—you experience the events from the first person perspective. In the second part, Bogart has a bandaged face—and this shows how distinctive his head is, which any half-informed cinephile will immediately notice, even under the bandage.

Only in the final part does the plot reveal the entirety of Bogart, who then quickly looks like Sam Spade in „The Maltese Falcon“—but here the star plays a prison escapee, Vincent Parry, an innocent convict who wants to go into hiding and even undergoes facial surgery to do so.

But of course the film is really just about the relationship with Lauren Bacall’s character Irene Jansen, about scenes that give us great, inimitable Bogart–Bacall moments. During filming, Bogart was bothered by increasing hair loss (due to stress and vitamin deficiency, as it later turned out) and in the end he even put on a wig in a panic.

-

Key Largo (1948)

Bildquelle: Warner Bros., Turner Entertainment

And another Bogart–Bacall film, this time their last: Frank McCloud is passing through and actually just wants to meet the relatives of his fallen war comrade when he falls in love with the widow and gangsters suddenly take over the entire hotel in the Florida Keys where they are now staying as a hostage.

In „Key Largo“—directed by Bogart’s friend John Huston, under whom he rose to stardom earlier in the decade in „The Maltese Falcon“—Bogart plays an aloof war veteran who falls in love and also has to stop the pistol-wielding narcissist Johnny Rocco (Edward G. Robinson).

The magical Bogart–Bacall romance unfolds across the screen one final time. The now real married couple sometimes only communicates through looks; Bogart is driving around the Florida coast in his shirtsleeves on a boat, Bacall smiling tenderly at him from the pier—almost like on the California coast in the Bogarts‘ real life.

-

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948)

Bildquelle: Turner Entertainment, John Huston, Point Blank

Bogart plays Dobbs, a drifter in Mexico who steals money from his fellow Americans but is tired of begging and dirty odd jobs. He teams up with two other fortune hunters to search for gold in the mountains. When they actually find what they’re looking for, Dobbs develops a paranoia so fundamental that it threatens everything they’ve achieved. Dobbs, infected with gold greed, is one of the meanest, most ruthless guys Bogart has ever played.

The otherwise stoic and cool Bogart, whose costume included a wig, harbors an uncertain mistrust of his character’s metamorphosis from a more affable adventurer to a deadly madman despite his infernally lit black and white face—but the old man, Walter Huston, stole the show and won an Oscar for Best Actor shortly before his death.

-

Knock on Any Door (1949)

Bildquelle: Santana Pictures, Columbia Pictures

In the first film for his new company Santana Productions, directed by his friend Nicholas Ray, Bogart played a noir lawyer who uses his legal knowledge to dismantle the witnesses in court while in real life he was in his late forties and awaiting the birth of his first child. His street background allows him to occasionally beat up a rebellious customer in the back alley.

Andrew Morton is a lawyer who has risen from the lower class and, out of a guilty conscience, takes on a difficult case, that of Nick Romano (John Derek), who is suspected of murder. In the courtroom, Morton acts as smartly as Bogart’s private investigators usually do on the street.

-

Tokyo Joe (1949)

Bildquelle: Santana Pictures, Columbia Pictures

With “Tokyo Joe,” Humphrey Bogart played the lead role in the first American film that was allowed to be shot in Japan, the country of the treacherous ex-enemy, after the Second World War.

Occasionally–including in his very first scene–Bogart speaks Japanese. On location, however, the travel-shy star was doubled by GIs who walked through the city in Bogart’s distinctive trench coat-fedora combination and were only ever seen from behind, while Bogart only met the Japanese population in rear projections.

Bogart is former Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Barrett, who wants to get his old nightclub back into operation, which he once owned before the war in which he himself fought against the Japanese. The ex-officer also meets his ex-wife (Florence Marly), who was believed to be dead, in Tokyo.

Even if the film cannot compete with previous Bogart works, his graceful look and his attitude when the new husband comes home to his ex-wife, his still great love, are great. And as always, Bogart gets involved with bad guys, this time to build a semi-legal but morally far less despicable business. Barrett’s on-screen insecurity around his daughter seemed close to Bogart’s discomfort with children in real life.

Interesting (spoiler alert): Bogie’s character in „Tokyo Joe“ is ultimately a loser by Bogart standards of those years. Although the veteran snatches his young daughter from the clutches of the gangsters, he loses the love of his life (to someone else) and his best friend (to harakiri death) before ultimately dying from gunshot wounds (so the last shot suggests).

“Tokyo Joe” shows how much Bogart has refined the role of the American fortune hunter in other parts of the world where occupiers or gangsters ruled, how he established the fedora, trench coat or flight jacket as habitual characteristics of the noir adventurer.

-

In a Lonely Place (1950)

Bildquelle: Columbia Pictures, Santana Pictures

Dixon Steele strikes faster than his opponent can insult him. The screenwriter is actually a sensitive soul, but after many years in the idiosyncratic Hollywood community, he is burdened with a lot of cynicism and pent-up aggression. Suddenly Steele is suspected of murder—and neither we as the audience nor his agent and his true love know exactly whether he is innocent.

Once again, the star tilts his head at the famous Bogart angle, with a cigarette tilted downwards and eyes turned upwards. From the minimalism of his extraordinary face, he conjures up an unexpected wealth of facets: the unpredictable thug who can easily be trusted with murder; the cool, sophisticated showbiz guy; the sensitive, caring lover—a man with mind and fist, psyche and physicality as alternating focuses.

-

The Enforcer (1951)

Bildquelle: United States Pictures

Prosecutor Martin Ferguson and police captain Frank Nelson want to put the head of a hit squad in the electric chair—he is already in a cell, but shortly before the trial they are short of witnesses.

The close-ups, the short tracking shots and the gentle noir look, especially the successful portraits of even the smallest roles, give ‘The Enforcer’ a gripping dynamic that makes the film stand out from the mass of crime films from the late 1940s and early 1950s. Bogart, in bow tie and fedora, once again shines as a tenacious gentleman detective who snoops his way past a mountain of corpses to the truth.

-

Sirocco (1951)

Bildquelle: Santana Pictures, Columbia Pictures

„You’re so ugly. Yes, you are. How can a man so ugly be so handsome?“ The fact that something like that could be said on screen to a (not unpretentious) star à la Bogart normally wouldn’t have been possible in the strict studio system of classic Hollywood. In “Sirocco,” Bogart continues the relaxed charm and hard-boiled ruthlessness of his leading roles of previous years: the nightclub owner Rick Blaine from “Casablanca” (1942) and the (unwilling human) smuggler Harry Morgan from “To Have and Have Not“ (1944).

In Sirocco, Bogart is once again a smuggler named Harry, this time with the last name Smith. In 1925, a brutal Syrian struggle for freedom against French military power was raging in Damascus—and Smith supplied the underground fighters with weapons; a war profiteer who only believes in money, but soon discovers the morals among all the money vultures in the city. In the scenes with the Swede Märta Torén, the trench coat veteran Bogart shows his flirtatious noir cool.

-

The African Queen (1951)

Bildquelle: Romulus Films

Humphrey Bogart, of all people, won his Oscar for a sensitive love story (albeit in an adventurously harsh setting), not for his archetypal private detectives and daredevils.

“The African Queen” shows him—for the first time in color—as stranded boat captain Charlie Allnutt, who gets caught up in the turmoil of the beginning of the First World War in Africa with the missionary Rose Sayer (Katharine Hepburn) and sails down a seemingly endless river in his old cutter—in the end they want to sink a German warship in patriotic enthusiasm.

„The African Queen“ is one of the few films for which Bogart left Los Angeles for an extended period of time—and as with „The Treasure of the Sierra Madre“ (1948) and later „Beat the Devil“ (1953), only John Huston knew how to get Bogart out of Los Angeles. During the strenuous filming far from civilization, unpleasant illnesses often occurred on set—almost everyone fell ill, except for Bogart and Huston of course, who clung to copious amounts of whiskey in the jungle.

Bogart’s unshaven, dirty alcoholic is a weary warrior, a lonely man who has difficulty eliciting unexpected kindness from his passenger. Almost like a method actor, the partially bearded Bogart marauds through the film in his sweaty, dirty clothes, which he never changes once—only his face when the radical teetotaler pours his gin reserves into the river does not seem to be acting.

-

Deadline – U.S.A. (1952)

Bildquelle: Twentieth Century-Fox

As the idealistic editor-in-chief of The Day—a daily newspaper that the founder’s heirs are about to sell for a better return on their fortune—Bogart fights for freedom of the press and the democratic empowerment of the population through critical journalism with the glamour of a recent Oscar winner as Ed Hutcheson.

Hutcheson is a brilliant journalist who is more married to his newspaper than he ever was to his ex-wife (Kim Hunter), and an incorruptible journalist who takes on a gangster boss whom he wants to convict of his machinations in public—Bogart as the mouthpiece of a pathetic plea for the American press.

-

Beat the Devil (1953)

Bildquelle: Santana Pictures, Columbia Pictures, Romulus Films

Billy Dannreuther, who is waiting on the Italian coast for a steamer to leave for Africa, is one of a group of dubious soldiers of fortune, of whom he still has moral decency.

Bogart, who produced the film with his company Santana Pictures, was once again persuaded by John Huston to film abroad—after the director read to him over the phone from the novel by an ex-communist on which the later film would be based. Bogart even agreed not to see his family and miss the baptisms of his two children—the three months were Bacall’s first long-term physical separation, as she was filming herself („How to Marry a Millionaire,“ 1953).

The close-ups at the beginning show us an authentic, unvarnished Bogart, with heavy bags under his eyes and wrinkled facial skin that the larger studio productions of the time would probably never have shown on screen in a star of Bogart’s stature.

“Beat the Devil”, which failed at the box office at the time, gained cult status over time and is considered the father of all cult films and shows a character who was probably closer to the real Bogart than most of his other roles.

-

The Caine Mutiny (1954)

Bildquelle: Columbia Pictures, SGS Corp.

When Maurice Micklewhite had to quickly decide on a new stage name in a telephone booth in Leicester Square because his previous stage name Michael Scott had been taken, he saw the new film of his idol Humphrey Bogart on one of the numerous cinema boards, after which he was now called Michael Caine.

In „The Caine Mutiny,“ Caine’s hero Bogart is an American ship commander in World War II whose psychosis endangers the lives of the entire crew.

Captain Philip Francis Queeg takes command of a minesweeper in the Pacific. The ship is battered and the crew is shattered. The experienced career officer Queeg—determined to do everything „by the book“, i.e. to follow the naval code meticulously—turns out to be a paranoid neurotic who senses hostility and intrigue directed against him everywhere, and small things lead to escalation and ultimately endanger his crew.

Bogart plays the broken commander, who in one scene turns to his officers with almost touching helplessness, only to shortly afterwards mutate back into a choleric despot, as a tragic figure. In his nervous phases he digs up a handful of marbles and then moves them frantically with his fingers. Triumphant gestures alternate with frightened, helpless facial expressions.

Bogart reluctantly accepted a lower fee than his star status actually deserved because he really wanted to play the role—with the bonus of a third Oscar nomination.

-

Sabrina (1954)

Bildquelle: Paramount Pictures

The brim of the hat can form a completely different figure: in one scene, the brim of the Homburg is folded down slightly and suddenly the serious scion of a very rich East Coast family becomes, for a brief moment, a noir figure, like the one Bogart portrayed several times embodied such unforgettable naturalness.

In fact, Bogart could easily be cut from this film and inserted into one of his noirs—no one would notice the difference. Director Billy Wilder actually wanted Cary Grant for the role of Linus Larrabee, the ascetic tycoon, head of a global multimillion-dollar company who can set entire fleets of ships in motion and send markets into panic with one phone call.

(Spoiler alert:) When his brother David (William Holden) falls in love with the chauffeur’s daughter, Sabrina (Audrey Hepburn), Linus intervenes with a delicate scheme and wins Sabrina’s heart so that David can marry the daughter of a company boss.

This ruthless trait of the deeply serious businessman as part of a brilliant joint venture masterminded by Linus Larrabee is something you immediately buy from Bogart’s performance. But the amazing thing is that this also applies to the following: Linus, the reserved romantic, falls in love with Sabrina. And there is always as much brightness in Bogart’s gloomy face as the pleasant characteristics of his characters require—a few millimeters of eyebrow movement is enough.

Newly crowned Oscar winner Humphrey Bogart didn’t have much fun with the film. When director Billy Wilder, Audrey Hepburn and William Holden put their heads together in the dressing room, he felt left out. He also didn’t like Wilder’s direction; and the two didn’t get along at all. Besides, the noir hero Bogart was afraid of appearing on the screen as a loser next to the playboy Holden.

In the 1995 remake, made forty years later, Harrison Ford plays the role of Bogart.

-

The Barefoot Contessa (1954)

Bildquelle: Figaro Inc.

Bogart in the pouring rain in a cemetery, without an umbrella but with a trench coat (and in colour), completely soaked at some point during the film. In „The Barefoot Contessa“, Harry Dawes narrates the events leading up to the mysterious funeral several times off-screen.

Dawes is a failed director and screenwriter, a sober alcoholic who has not been hired in Hollywood for a long time because of his drinking failures, which is why he is at the mercy of his new employer, the multimillion-dollar heir Kirk Edwards (Warren Stevens)—an allusion to the multimillion-dollar heir and producer Howard Hughes—and his plutocratic whims.

Dawes has the most polished lines in the film, a sage among adventurers. And he becomes the confidante of the new star, Maria D’Amato (Ava Gardner).

-

We’re No Angels (1955)

Bildquelle: Paramount Pictures

As Joseph, one of three escaped prisoners on Devil’s Island in French Guiana at the end of the 19th century, Bogart plays one of his rare comedy roles in „We’re No Angels“—and in a Christmas film. And as if all that wasn’t enough, he also serenades his two accomplices in the chorus.

Dressed in rags, the criminal is a gifted manipulator of business books and a cunning salesman who even sells a comb and brush set to a bald customer.

The fact that a rapist and a murderer were suitable film heroes alongside Bogart’s swindler does not change the fact that the whimsical theatre adaptation has aged in the memory of many people as one of the best Christmas films.

Unlike shortly afterwards in „The Desperate Hours“ (1955), his envy of his family’s happiness does not lead to hatred, but to love. Because Joseph has his heart in the right place—instead of robbing (and perhaps even murdering) a merchant’s family, he and his two companions (Peter Ustinov and Aldo Ray) help the Ducotels achieve even greater happiness.

-

The Left Hand of God (1955)

Bildquelle: Twentieth Century-Fox

In „The Left Hand of God„, Bogart wanders through a matte painting Asia in 1944 that seems a hundred times more authentic than the majority of studio productions of the time. Dressed in the black robes of Priest O’Shea, he appears as an enigmatic man in a remote Catholic mission, blesses his way into the hearts of the villagers and plays a crap game with a Chinese warlord over the fate of his community.

Bogart speaks Chinese (in a sermon) and sings a duet with Gene Tierney in the midst of a pack of children—a performance in which he charmingly combines his rhetorical and physical repartee as the centre of an entertaining adventure drama.

-

The Desperate Hours (1955)

Bildquelle: Paramount Pictures

For all those who had not yet realised it (and for posterity), the antagonist in „The Desperate Hours“ illustrated the range of Humphrey Bogart’s acting: Glenn Griffin, the homicidal escapee who takes an entire family hostage on his escape with his two accomplices and whom only a gifted screen psychopath like Mickey Rourke dared to tackle in the 1990 remake.

With an almost sadistic lust, Bogart’s fugitive criminal shatters the suburban family idyll of the Hilliards, whose established bourgeoisie he tyrannises with relish—because they lead the life that society has denied him and other criminals.

Bogie’s unceremonious transformation from the noir elegance familiar from so many films up to that point, from unashamedly cool restraint to morally squalid bandit shabbiness. Bogart acts here as if he is savouring every single moment of this nasty role.

And Bogart’s willingness to play a murderous creep à la Griffin also shows how, even as a star, he was not too bad for a role in which, among other things, he presses a pistol to the head of a little boy.

„The Desperate Hours“ was filmed several more times: 1967 as a television film (with George Segal in Bogart’s role) and in 1990 with Mickey Rourke as Bogart’s successor.

-

The Harder They Fall (1956)

Bildquelle: Columbia Pictures

Eddie Willis, worn down by his decades as a sports journalist and seemingly failed once and for all, gets himself hired as a PR agent by sleazy boxing promoter Nick Benko (Rod Steiger)—to write up a naive amateur (Mike Lane) as an invincible boxing champion and finally earn the big bucks.

The spin doctor, who gives his protégé a CV suitable for the mass media, nevertheless proves in the end that his heart is in the right place. In his last film, Bogart’s face manifests above all Eddie Willis‘ shock at having served as an accomplice to filthy greed for far too long.

Presumably already plagued by the pain of his fatal illness, Bogart unknowingly played his last role. Taking this into account, one sometimes seems to recognise the agony in his gaze, his facial expressions. And as if Bogart wanted to burn a personal signature into the screen for eternity, he has a cigarette hanging from the corner of his mouth in his very first scene (the film is only in its third minute).

Text: Robert Lorenz