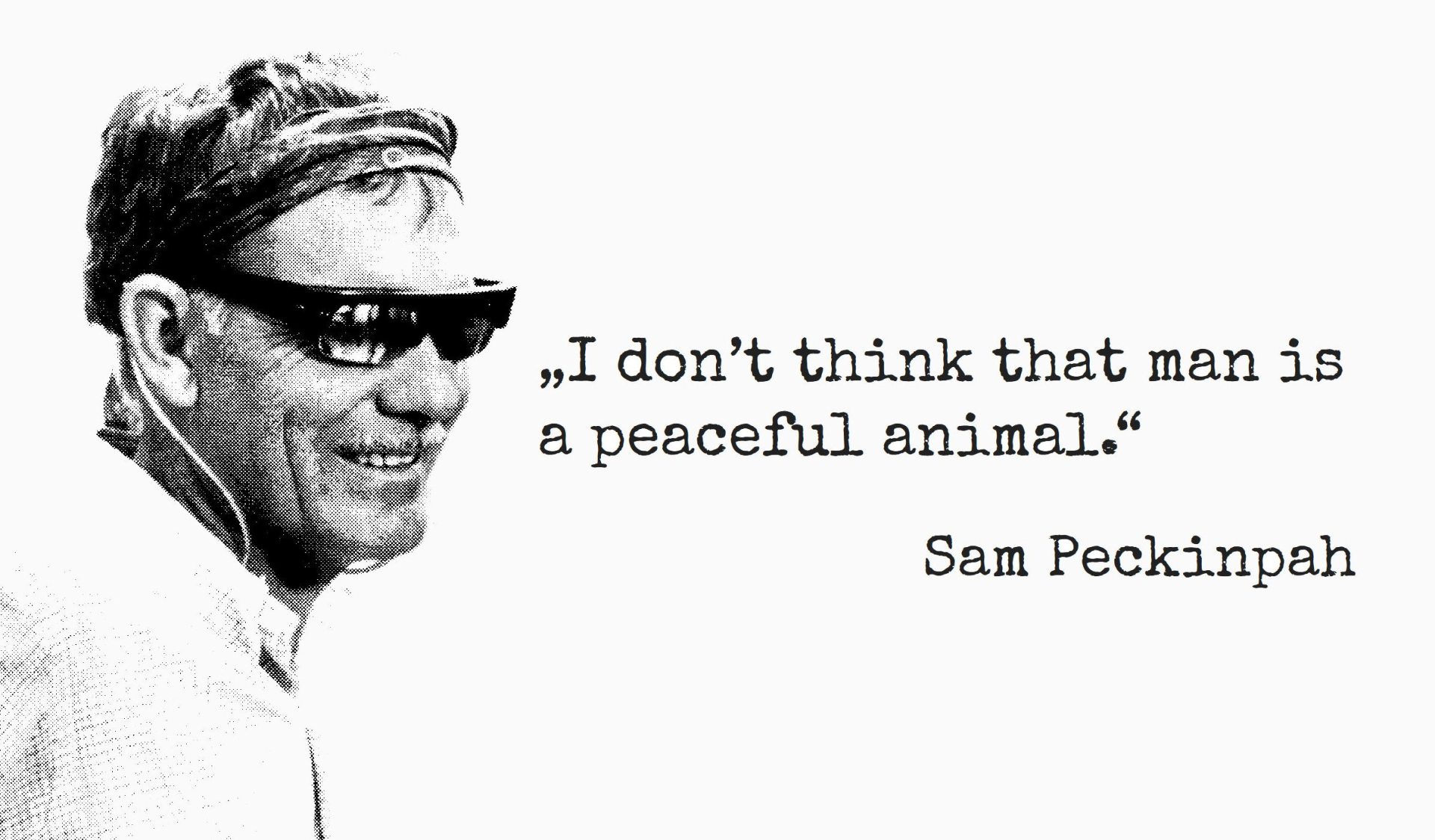

The Films of Sam Peckinpah

Social-Media-Optionen

The melancholy of the Old West shortly before its downfall, the bigotry of corrupt elites, death in slow motion: Sam Peckinpah’s films thrilled or disturbed critics and could send entire cinema halls into shock or bloodlust, but they left no one cold—a retrospective.

All films by Sam Peckinpah

-

The Deadly Companions (1961)

Peckinpah’s film debut

Bildquelle: Carousel Prod. Inc., Lakeshore Int. Corp.

The plot: A Civil War veteran escorts a widow through hostile Apache territory so that she can bury her slain son in a ghost town.

With „The Deadly Companions„, TV series director Sam Peckinpah made the leap from the screen to the big screen.

„Bloody Sam’s“ film debut is clearly more a commission than his own work—where later in his films bodies are ripped apart by bullets with brute slowness, Peckinpah’s influences here still seem like timid attempts to break commercial conventions, but nevertheless reveal this filmmaker’s extraordinary talent for staging.

-

Ride the High Country (1962)

Peckinpah recommends himself for Hollywood

Bildquelle: MGM, Turner Entertainment

The plot: Two frontier veterans (gravely cast with genre veterans Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott) are long past their prime when they get hired by a bank to protect a gold shipment from bandits in the Sierra Nevada mountains.

„Ride the High Country“ already flashes the brilliance of „The Wild Bunch„, the great Peckinpah Western: the melancholy of aged westerners and their companionable path to ruin.

In retrospect, one can see how here a young director is using an inherently hackneyed Wild West plot to surreptitiously inject a dirty realism into the Western as a vaccine against the eternal clichés of a long tradition of soft-boiled Hollywood films—in „Ride the High Country“ everything is a touch more rancid, more worn out than in other Westerns. There is the mangy rain jacket of one of the two protagonists, plagued by back and foot pain; the judge—almost always a person of respect in Westerns—is a sweaty drunk and the former gunslinger needs glasses to read.

-

Major Dundee (1965)

Bildquelle: Columbia, Jerry Bresler Productions

The plot: In the middle of the American Civil War, a Northern cavalry commander leads a squad to Mexico to hunt down an Apache chief.

After his first two films had cost him a lot of nerves in the clinch with studio bosses and producers, „Major Dundee“ turned into Peckinpah’s fierce Hollywood trauma.

What could have been the film of his life was, in Peckinpah’s eyes, in the end a celluloid torso dismembered by incompetent fangs, „one of the most painful things that has ever happened in my life“[1]. Despite the heavy use of studio scissors, „Major Dundee“ dismantled the cinematic myth of the heroic cavalry and featured a remarkably shady protagonist in Charlton Heston’s officer, who goes into battle with drunken scoundrels.

[1] Peckinpah quoted after Whitehall, Richard: Talking with Peckinpah (1969), in: Hayes, Kevin J. (Hg.): Sam Peckinpah: Interviews, Jackson 2008, pp. 46–52, here p. 51 [highlighting in the original].

-

Noon Wine (1966)

Peckinpah’s comeback film

Bildquelle: Talent Associates

The plot: When the enigmatically silent but hard-working drifter Olaf Helton hires on at the Thompson farm, the disintegration of a family takes its course.

After the temporary end of his Hollywood career, Peckinpah took refuge where he had come from: in television. With his decelerated TV western „Noon Wine„—strongly cast with Broadway grandee Jason Robards and Hollywood aristocrat Olivia de Havilland—he showed how a single violent outburst can shatter a person’s life, and in the process rehabilitated himself as a director and screenwriter.

-

The Lady Is My Wife (1967)

Peckinpah’s theatrical film

Bildquelle: Hovue Productions

The plot: A Southern couple, two Civil War losers, arrive in a ghost-town Western nest in the North—the ex-colonel’s rigid adherence to yesterday’s values and notions of honour threatens his marriage to his wife, who is coveted by a heavily wealthy rancher.

After Peckinpah was back in the game with his critically acclaimed „Noon Wine“ success, he made another TV movie for Universal, which he garnished with his now typical undertones and details—almost like a play.

-

The Wild Bunch (1969)

Peckinpah’s quintessence of the Western

Bildquelle: Warner Bros.-Seven Arts

The plot: In 1913, a gang of outlaws gets caught between the fronts of the Mexican Civil War, pursued by relentless bounty hunters.

After the debacle of „Major Dundee“ and his expulsion from „The Cincinnati Kid“ (1965), Peckinpah, excommunicated from the film industry, fought his way back to Hollywood via television. „The Wild Bunch“ became the film he had already wanted to make with „Major Dundee„, and with its study of human brutality is something like the quintessence of Peckinpah cinema. In parts the portrait of a romantic-melancholic outlaw camaraderie, the film culminates in a grotesque inferno of violence as a brutal counterpart to the classic Hollywood Western.

-

The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970)

Peckinpah’s love story

Bildquelle: Phil Feldman Productions, Warner Bros.

The plot: On the eve of the automobile age, fortune hunter Cable Hogue finds a waterhole in the middle of the desert with which he plans to supply stagecoaches. While building the desert watering hole „Cable Springs“, the stalwart desert entrepreneur falls in love with the prostitute Hildy.

In the violence-intensive Peckinpah oeuvre, „The Ballad of Cable Hogue“ is something of a romantic comedy.

The Western fairy tale shows loneliness and deceitfulness as social constants of the Old West; and even more than the title (anti-)hero, the film is about the prostitute, who in Peckinpah’s cinema, contrary to common moral concepts, is always the only sincere person anyway.

-

Straw Dogs (1971)

Peckinpah’s scandalous film

Bildquelle: ABC Pictures, Eldorado Films

The plot: When a young mathematician in the remoteness of a southern English farmhouse fights off a drunken lynch mob from the nearby village, violence escalates mercilessly.

From the very first second of the film, Peckinpah unleashes an underlying threat potential in „Straw Dogs„, which is eventually detonated by a mixture of primitive vigilante desires and the awakening of an archaic will to assert oneself.

The explicit depiction of violence—from a relentless rape sequence to the streams of blood flowing from the bullet wounds of mutilated bodies—makes this film, which outraged contemporary moralisers, a complex study of human brutality.

-

Junior Bonner (1972)

Peckinpah’s family drama

Bildquelle: ABC Pictures, Wizan Productions, Solar Productions

The plot: In Prescott, Arizona, for returning ex-rodeo champion Junior Bonner, family conflicts are as exhausting as riding furious bulls.

„Junior Bonner“ inspects the peculiar rodeo milieu as a semi-anachronistic element of society—archaic masculinity rituals and carefree voyeurism. Hollywood warhorses Ida Lupino and Robert Preston steal the show even from Steve McQueen’s jaded stoicism.

-

The Getaway (1972)

Peckinpah’s commercial action thriller

Bildquelle: Solar Productions, David Foster Productions, National General Pictures

The plot: Professional bank robber „Doc“ McCoy, out on parole, is supposed to rob a bank for a businessman—the prelude to a series of violent complications.

After their box-office flop „Junior Bonner„, scratched Hollywood star McQueen and perennially faltering director Peckinpah tried a second time—and this time landed a gigantic box-office hit that grossed ten times its cost.

-

Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (1973)

Peckinpah’s dismantling of a myth

Bildquelle: Turner Entertainment, Warner Bros.

The plot: In late 19th century New Mexico, ex-gangster Pat Garrett, now a man of the law, hunts down gunslinger Billy the Kid, with whom he has an almost paternal relationship.

Sweaty Western violence, death in slow motion and Bob Dylan: „Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid„, for which supporting actor Dylan wrote „Knockin‘ On Heaven’s Door„, Peckinpah used less as an unembellished depiction of a US Wild West myth than as a look at the law as a stretchable instrument of morally depraved elites.

-

Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974)

Peckinpah’s project of the heart

Bildquelle: MGM

The plot: Bounty hunters pour out to bring the head of Alfredo Garcia to a Mexican patriarch—a million dollars awaits.

„Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia„, the infernal road trip of the washed-up bar pianist Bennie, played so brilliantly by Warren Oates, is perhaps Peckinpah’s most personal film, with and the sentimental portrait of Mexico and the love story buried among all the meticulous depictions of violence.

-

The Killer Elite (1975)

Peckinpah’s martial arts persiflage

Bildquelle: MGM, Exeter Associates

The plot: invalid secret service agent Mike Locken fights his way back into his old job with a cane to get revenge on his treacherous partner.

When Peckinpah made „The Killer Elite„, his directing career was already in decline—and as if to confirm this, the film failed with most critics. Yet the film, garnished with contemporary, popular martial arts elements, unfolds its very own charm, not least because of the great cast with noble supporting actors and the superbly photographed setting of San Francisco.

-

Cross of Iron (1977)

Peckinpah’s anti-war film

Bildquelle: Rapid Film

The plot: Sergeant Rolf Steiner leads a platoon of hardened front-line pigs through the cruel retreat battles of the Eastern Front at the Kuban bridgehead in the summer and autumn of 1943.

With its delirious battle scenes, „Cross of Iron“ is one of the most intense anti-war films ever made. One should be grateful that Peckinpah’s staging of gun violence has also taken on the Second World War and that the miserable slow-motion deaths of the soldiers capture the madness of war.

The fact that the excellently cast „Cross of Iron“ also explores the simultaneity of egoistic order hunters and command receivers deformed into professionalised survival fighters is then almost a minor matter.

-

Convoy (1978)

Peckinpah’s road movie

Bildquelle: Studiocanal

The plot: The desperate self-defence of a handful of truckers under their charismatic leader „Rubber Duck“ against the police violence of a sleazy Heartland sheriff escalates into a politically tinged truckers’ protest and mass media event.

In retrospect, the 18-tyre roar of the rebellious truck drivers appears as an outlet for the frustrated US working class at the end of the 1970s.

Peckinpah followed the filming as an erratic drug wreck, which contributed to the indecisive effect of his penultimate work, as did the assumption of the final cut by hands other than the director’s—which was probably due to the fact that he secretly thought the project was doomed to failure early on. Nevertheless, there were ingeniously crazy-martial road-trip images.

-

The Osterman Weekend (1983)

Peckinpah’s view at the observation society

Bildquelle: Osterman Weekend Associates, Concorde

The plot: A television journalist learns from the CIA that his best friends are communist traitors in the service of the KGB whom he must now spy on.

Like a mirror of the director himself, who gave up excessive smoking and drinking after a heart attack, „The Osterman Weekend“ seems far less intense than earlier works. Instead, it proves to be an interesting conclusion to the sobering decade after „Watergate“ and a pessimistic preview of a secret bureaucracy technologically capable of opaque surveillance.

Text: Robert Lorenz