The Best Western Movies of All Time [a Selection]

Social-Media-Optionen

A selection of the best western films of all time, focused on Hollywood productions—the numbering of the list does not indicate a ranking, but is merely for orientation.

Our pick of the best western movies of all time:

-

The Hunting Party (1971)

Bildquelle: Brighton Pictures, MGM

The plot: outlaw gunslinger Frank Calder is the leader of a gangster squad and kidnaps a supposed schoolteacher, who turns out to be the wife of the completely scrupulous self-made man Brandt Rutger—unawares, the outlaws are hunted by a posse with deadly long-range rifles.

Brutal to the hilt, and yet with Gene Hackman, Candice Bergen and Oliver Reed in the Hollywood mainstream flowed: „The Hunting Party“ is certainly not the Western that you expect from the dream factory. This movie combines the uncompromising brutality of a Sam Peckinpah and the dirty morals of the Italo Western.

-

Ulzana’s Raid (1972)

Bildquelle: Universal Pictures

The plot: Apache leader Ulzana escapes from a reservation with a handful of warriors to strike Arizona and its homesteaders with a gruesome killing spree. The military sends a cavalry unit to stop the marauding Indians.

If „The Hunting Party“ is still too lax in terms of Western brutality, Robert Aldrich’s „Ulzana’s Raid“ will overwhelm you. In his carefree maverick attitude, Aldrich lets nothing and no one get away. The U.S. Cavalry gets completely robbed of its Western myth—which not only amounts to a genre dismantling, but could also be understood as an allusion to the Vietnam War at the time.

Burt Lancaster plays the scout filled with bitter wisdom who is supposed to lead the cavalrymen to the Indians—a figure in which Lancaster thought he recognized himself. Quite untypically, the Indians are not staged as shooting gallery figures, but as precisely operating guerrilla fighters.

-

McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971)

Bildquelle: Warner

The plot: With a handful of prostitutes frontier entrepreneur McCabe moves to a godforsaken small town to open a brothel.

In the finest New Hollywood manner, Robert Altman takes apart the Western genre. The harmony of cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond’s images and Leonard Cohen’s score is ingenious; and rarely has the scenery of a Western been so inhospitable due to the coldness (of both climate and society) as in „McCabe & Mrs. Miller„.

-

Jeremiah Johnson (1972)

Bildquelle: Warner Bros., Sanford Prod.

The plot: In the middle of the 19th century, ex-soldier Jeremiah Johnson seeks his fortune in the nowhere of the snowy mountains of Colorado and becomes the idée fixe of an Indian vendetta.

If „McCabe & Mrs. Miller“ hasn’t sufficiently disillusioned you with Western topography, „Jeremiah Johnson“ certainly will, at the latest, with its cold woods, wild wolves and grizzlies.

The title character is a frontier greenhorn who turns away from a self-destructive civilization at the price of an unrelenting struggle for survival. While asserting themselves under extreme conditions, not only is the frontier pioneers’ prowess as daring loners revealed, but also the murderous selfishness of the settlement movement. The multiple times proven Pollack/Redford combination portrays the path to a new life as an endless odyssey full of death and hardship.

-

The Hired Hand (1971)

Bildquelle: Pando Company, Koch Media

The plot: After many years of nomadic existence in the US Southwest, Harry Collings returns home to his wife, before whom he tries to redeem himself for his absence as a simple laborer on the farm. Then his partner Arch Harris is kidnapped because of an old feud, and Collings must decide to whom his attachment is greater: his wife or his friend.

In their cry for help, the major studios at that time gave young filmmakers like Peter Fonda money and final cut privileges, so that they could once again bring about a box office miracle à la „Easy Rider“ (1969). Of course, „The Hired Hand“ was far from achieving the desired victory at the cinemas—but still for Western lovers the film is a little treasure.

In Fonda’s westerns, there is hardly any talking, occasional shooting, a lot of riding and silence. The film shows the completely unromantic reality of homesteaders, the taciturn camaraderie of vagabond cowboys and the tribulations of heroism. Experimental editing, Vilmos Zsigmond’s camera and an unconventional showdown make „The Hired Hand“ a somewhat different Western.

-

Johnny Guitar (1954)

Bildquelle: Republic Pictures

The plot: Saloon owner Vienna must defend herself against a posse that her rival Emma uses for a private feud.

Of all things, Hollywood of the male-dominated studio era produced one of the most feminist films ever: In „Johnny Guitar,“ women hold the revolver. Joan Crawford’s frontier businesswoman Vienna prefers to listen to the wheel of her roulette table; but when her vengeful antagonist, embodied by the later „Exorcist„ demon Mercedes McCambridge, burns down the saloon and wants to string Vienna up, a destructive duel breaks out between the two women that relegates even the toughest gunslingers to supporting characters.

-

Forty Guns (1957)

Bildquelle: Twentieth Century-Fox

The plot: Jessica Drummond rules Cochise County with her fortune and her forty armed horsemen. Her little brother is a revolver-wielding troublemaker who comes into conflict with the Bonnell brothers, whose head is the dreaded gunman Griff Bonnell—a man who has sworn off killing but is forced to take up arms again by the juvenile delinquent Drummond.

A character who would be a man in any other Western before and long after: Barbara Stanwyck plays a merciless matriarch who has bought sheriff and judge, keeps a killer brigade as her court, and engages in salacious dialogues with ex-gunslinger Bonnell, whose revolver she wants to touch and who—against all customs Hollywood westerns—is the love-interest in the film. The Western with the prairie plutocrat in the wicked Arizona Territory is one of Hollywood’s few feminist blossoms.

-

Cat Ballou (1965)

Bildquelle: The Harold Hecht Corp., Columbia Pictures

The plot: The father murdered, the family dispossessed—the farmer’s daughter Cat Ballou swears revenge, becomes an outlaw and wants to hunt down with the help of a gunslinger the hitman of the big investor who took everything from her.

The moral gloom of the Wild West with revenge, corruption and the inflationary use of capital punishment is here cloaked in the format of a comedy. Lee Marvin plays a drunken gunslinger whose horse staggers along with him, when Marvin himself was an alcoholic—for this performance he received, rightly, an Oscar.

-

Two Mules for Sister Sara (1970)

Bildquelle: Universal

The plot: Hogan saves a nun from being raped by a handful of scoundrels—afterwards the woman involves him in the Mexican fight for freedom against the French army while he wants to get hold of a pile of gold.

One of Shirley MacLaine’s best flicks is not alongside Jack Lemmon directed by Billy Wilder, but alongside Clint Eastwood directed by Don Siegel. The film, in its Italo-Western look, appropriately underscored by a Morricone score, shows a woman using her sex appeal to involve an ideologically disillusioned loner in the collective struggle, mercilessly manipulating him despite all his coolness and cultivated egotism.

-

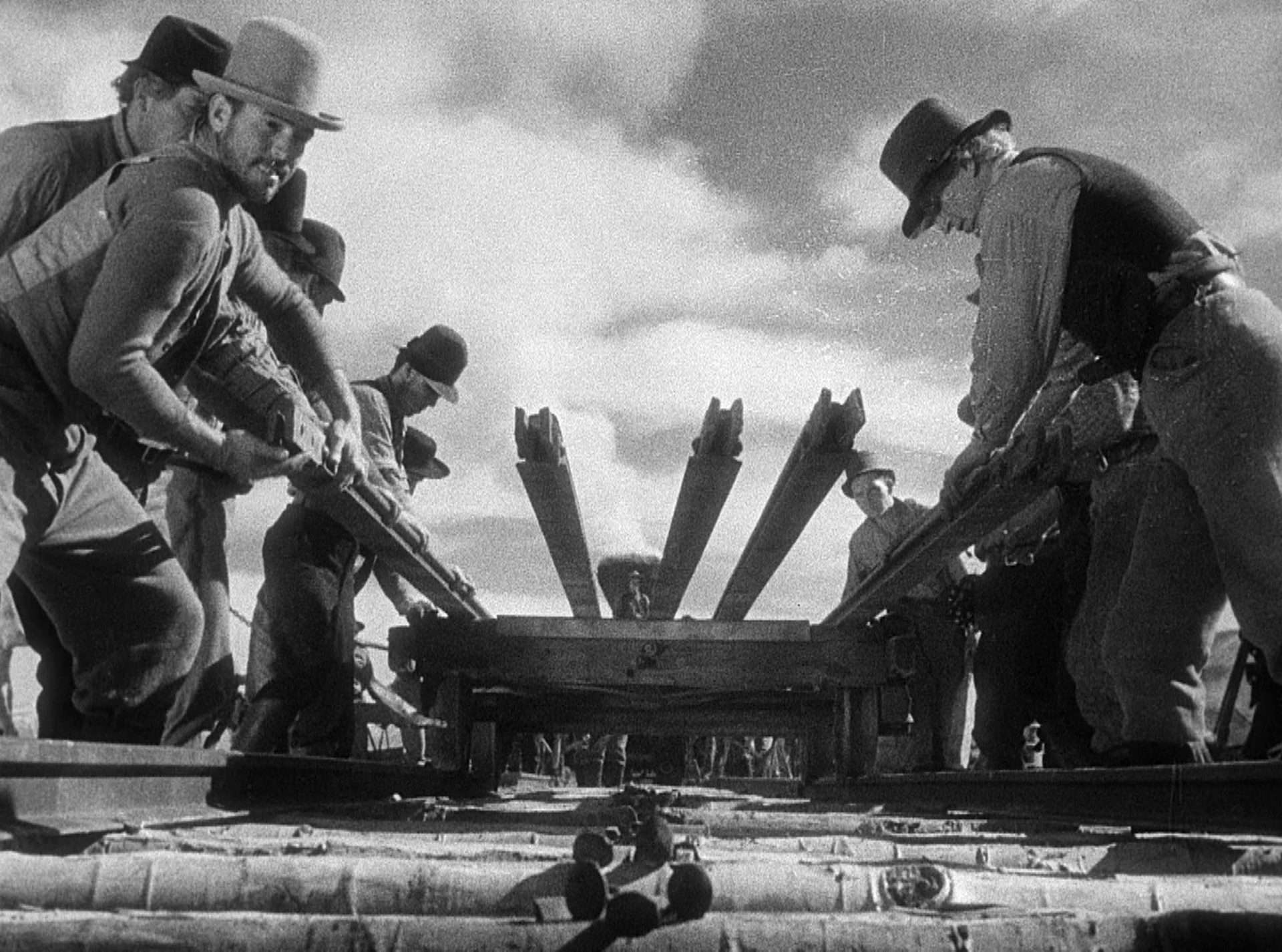

Union Pacific (1939)

Bildquelle: Paramount Pictures, EMKA

Shortly after the American Civil War, a decision is made in Washington to build a railroad across the U.S. to connect the East and West. Secretly, the greedy speculator Barrows tries to undermine the historic project by having a gambling casino travel along—which is supposed to entice the railroad workers into gambling. The railroad company hires a troubleshooter to drive the crooks away.

More frontier flair in a movie is hard to find: Whether Indian attacks, saloon gunfights or coyote howls, The Railroad ode „Union Pacific“ helped formulate all the clichés and motifs that late Westerns and New Hollywood cinema later deconstructed. The film by Hollywood co-founder Cecil B. DeMille is a brilliant screen spectacle of monumental proportions, which is worthwhile above all as a very classic Western.

-

How the West Was Won (1962)

Bildquelle: Turner Entertainment

The plot: The fate of a European immigrant family is used to portray the grueling settlement of the U.S. Southwest over several decades.

How the people got to their farms and ranches in the first place is shown in „How the West Was Won.“ Garnished with countless well-known names, the film is an epic tour de force that shows in several episodes—staged by several directors—the adversities of the settlement of the North American expanse by European emigrants.

The spectacular tracking shots, scenes like paintings, gigantic panoramas and haunting perspectives may not be realistic, but convey a vague sense of all the hardships that preceded what is now the United States—with raft trips through raging rivers and the settler treks to even get to the remote areas that were then opened up with railroads, taken from the Indians and devastated in the Civil War.

-

Ride the High Country (1962)

Bildquelle: MGM, Turner Entertainment

The plot: Two frontier veterans (gravely cast with genre veterans Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott) are long past their prime when they get hired by a bank to pick up a gold shipment in the Sierra Nevada mountains.

„Ride the High Country,“ considered the first true Peckinpah Western, celebrates the melancholy of aged Westerners and their fate-tanned male friendship. Peckinpah, who had spent large parts of his childhood in a similar area, not only garnished his film with autobiographical elements (Joel McCrea’s Steve Judd is modeled on Peckinpah’s father in terms of character), but also enriched it with an incredible wealth of detail that often only becomes apparent on a second or third viewing—in „Ride the High Country“ everything is a bit more mangy, more weathered, even the bullet hole in a window pane seems more brute and realistic than in most other Westerns. And the finale, a foretaste of the elegy of „The Wild Bunch,“ can confidently be described as the poetic quintessence of the Western.

-

High Noon (1952)

Bildquelle: Stanley Kramer Prod., Fernsehjuwelen

The plot: On the day of his departure and wedding to a Quaker woman, of all things, Will Kane finds himself forced to pin on his marshal star once again to face the outlaw Frank Miller, who will arrive in town on the noon train.

Fred Zinnemann’s „High Noon“ is not only one of the ultimate film classics, but has lost nothing of its freshness, elegance and intensity—there are few films from the fifties that the decades have passed by without leaving such a trace. The spartan musical accompaniment and silent close-ups, blended with the otherwise often anachronistic black-and-white, give „High Noon“ a gripping surreal aura.

Zinnemann and his crew deliver a composition that ticks as precisely as the clock that indicates the approaching showdown. The heart of the film is the selfish ingratitude of the hardworking small-town community whose members abandon the very one to whom they owe everything—U.S. civil society as a cowardly bunch.

-

Will Penny (1967)

Bildquelle: Paramount

The plot: Will Penny is a real cowboy, a cattle drover whose nomadic existence leads him through endless loneliness until he falls into the care of a single mother who, for the first time in his life, questions brutal selfishness as a survival strategy.

Although it by no means stands out from his body of work, „Will Penny“ is the film that best reveals Charlton Heston’s acting greatness. The title character, Will Penny, is a counter-representation of the clichéd Westerner so often portrayed by John Wayne—a washed-up man who learns the value of family cohesion more at the end of his life than at the beginning.

The film begins on the barren prairie and leads to the foot of the Sierra Nevada with its mountain forests, where only the hardy survive—a look at the darker side of individuality, mobility and flexibility, at the end elegiacally sung by Don Cherry.

-

The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970)

Bildquelle: Warner Bros.

The plot: In the face of death, prospecting entrepreneur Cable Hogue finds a watering hole with which to become a desert entrepreneur on a stagecoach trail. He overcomes his loneliness with the prostitute Hildy.

What a sentimentalist „Bloody“ Sam Peckinpah, who relentlessly confronted his audience with scenes of violence and regularly aroused the ire of moralists, had been in reality is shown by „The Ballad of Cable Hogue„—a sensible love story in the rough scenario of the Wild West.

The West that Peckinpah depicts here is, of course, on the eve of a turning point, its downfall; in one scene, the men, accustomed all their lives to horseback riding, marvel at the arrival of an automobile. The story of Cable Hogue’s desert watering hole is not least a fabulously veiled look at loneliness and deceit as social constants of the Old West.

-

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969)

Bildquelle: Twentieth Century Fox, Campanile

The plot: The two outlaws Butch Cassidy and Sundance Kid rob banks and trains until they escape from the superiority of a railroad tycoon to Bolivia, where they try continuing their criminal career.

The fact that the Hollywood Western not only told fairy tales, utopias and fictions, but also drew on real figures and events here and there is shown, for example, by „Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,“ through which a certain young actor named Robert Redford became a star virtually overnight. Redford and his already established screen partner Paul Newman play two of the most charming outlaws in film history, who in a legendary scene at the end rush into the shootout as if there were no tomorrow.

-

Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (1973)

Bildquelle: Turner Entertainment, Warner Bros.

The plot: Sheriff Pat Garrett is supposed to hunt down his old companion Billy the Kid, who keeps refusing Garrett’s offer to escape to Mexico.

Sheriff Baker crouches on a stone, doomed by a shot in the stomach, in the background floats—at first softly, then louder and louder—the music, which today everyone knows, but at that time was only written for this scene—“Mama, take this badge off o’ me, ’cause I can’t use it anymore. It’s gettin’ dark, too dark to see. I feel like I’m knockin’ on Heaven’s door.“ Bob Dylan, then, in his screen debut, plays a man with no name, simply called „Alias,“ Slim Pickens, who barely ten years earlier rode the atomic bomb like a Texas bull for Stanley Kubrick, the dying sheriff.

In the manhunt between Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, like Cassidy and Sundance historical figures, they are merely supporting characters; James Coburn and Kris Kristofferson play the title roles—and damn well. Sam Peckinpah uses the material to deal with the depravity of the establishment and the senselessness of gun death in a multifaceted Western. And as in „The Wild Bunch„, the director shows the recurring brutalization of society by means of innocent children, who here gleefully swing the gallows rope and are socialized with the violent acts of adults

-

‚Doc‘ (1971)

Bildquelle: Frank Perry Films, Black Hill Pictures

The plot: Power-conscious lawman Wyatt Earp and consumptive poker ace Doc Holliday want to gut a mining town in swashbuckling Arizona Territory—getting into an escalating conflict with the Clanton brothers.

Another Western myth that Hollywood has managed to exploit commercially is the gunfight at the O.K. Corral in 1881—an example that sometimes it is indeed the victor who writes the story. In this case, it is Wyatt Earp, who, as the survivor of the shootout with the Clanton gang, subsequently styled himself as a law-and-order preserver.

After earning money from the Earp myth for forty years with several films, Hollywood now again earned money from its deconstruction. In the New Hollywoodesque „Doc,“ the Earp mythology is so thoroughly dismantled that the hitherto morally impeccable Earp faction is not only plunged into twilight, but the confrontation with the Clantons appears as a self-righteous execution

-

The Missouri Breaks (1976)

Bildquelle: United Artists, MGM Home Entertainment

The plot: A gang of hardened horse thieves is targeted by a so called „regulator“ hired as a factual contract killer by a large landowner.

„The Missouri Breaks“ is first of all formidably cast: with Harry Dean Stanton, Jack Nicholson (with a beard!), Randy Quaid or even John P. Ryan as professional bandits, Kathleen Lloyd as a farmer’s daughter who takes up with one of them. But the highlight of the film is Marlon Brando as the eccentric sadist Robert E. Lee Clayton, who gleefully rounds up the criminals. Free of pathos and romance, „The Missouri Breaks“ works out the archaic brutality of hard-hearted frontier America.

-

The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976)

Bildquelle: Warner Bros.

The plot: After the family of farmer Josey Wales is murdered by a Northern soldier corps during the Civil War, Wales even resists surrender to continue hunting down the perpetrators. In his fight for revenge and survival, he crosses the endless expanses of Texas and Kansas as an outlaw.

Like the Vietnam War at the time of filming, the American Civil War once produced efficient killing specialists who then found no use in peacetime. While shooting countless people on his journey through the U.S. Heartland, Clint Eastwood’s revenge rider gathers a whimsical entourage of diverse people around him, dissolving the fractured postwar era into a kind of Western utopia of a multicultural small community.

-

Stagecoach (1939)

Bildquelle: Walter Wanger Prod.

The plot: A stagecoach becomes the gathering place for social outcasts who must band together to form a survival community when they are attacked en route by hostile Apaches.

For some, „Stagecoach“ is the ultimate Western: the strangers to each other—the fugitive gunslinger, the marshal, the coachman, the whore, the pregnant woman, the boozy doctor, the criminal banker, the whiskey salesman and the gambler—who must take their fate into their own hands in the face of murderous Indians. „Stagecoach“ is the film with which John Ford stylized Monument Valley, located on the border between Arizona and Utah, into an archetypal Western panorama—and a largely unknown Western actor named John Wayne began his rise to Western stardom

-

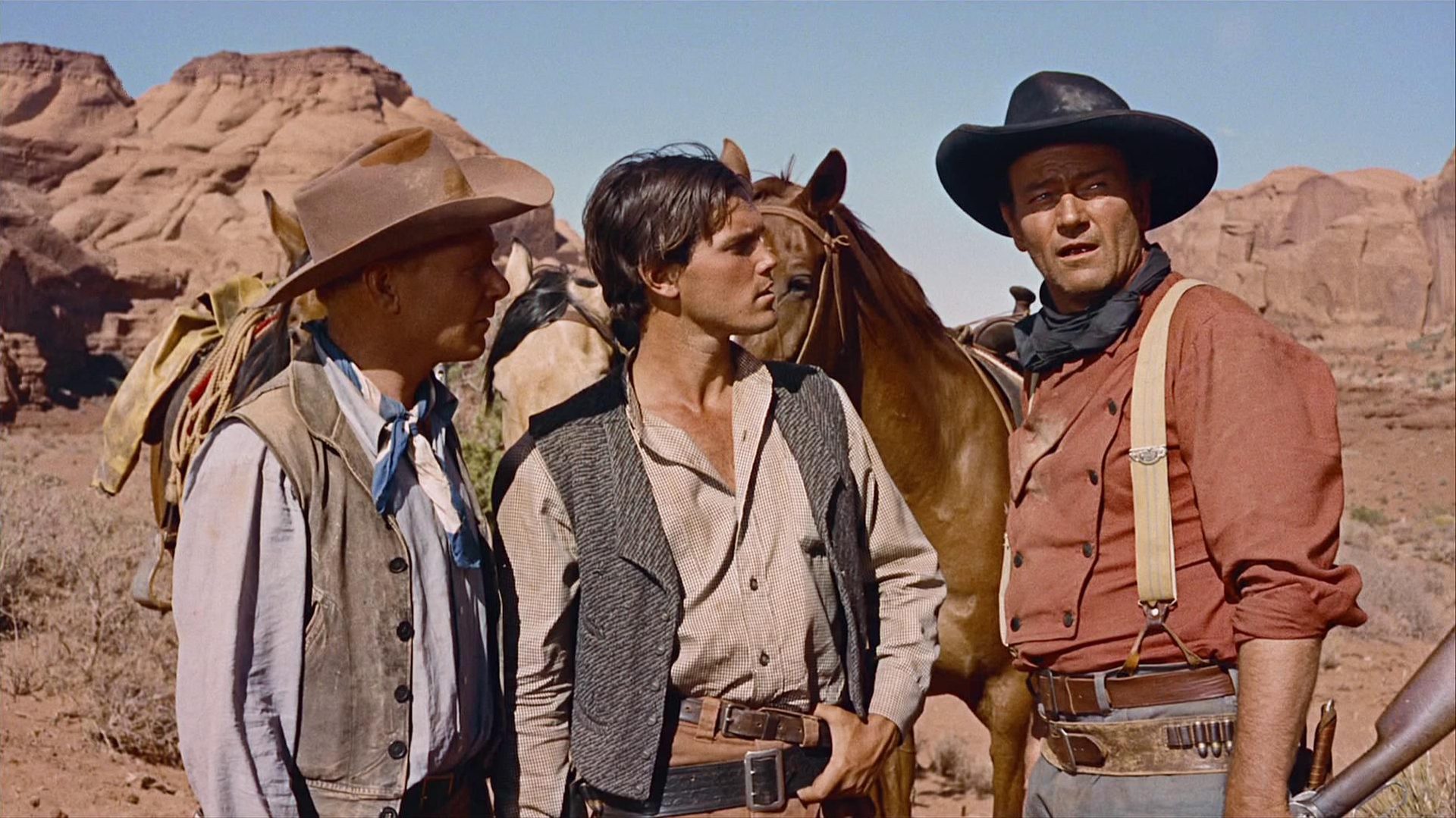

The Searchers (1956)

Bildquelle: Warner Bros.

The plot: Civil War veteran Ethan Edwards returns home to his brother and his family, who are wiped out by Comanches shortly thereafter. Only the little niece has survived and Edwards begins a search for her, which lasts several years.

Another Ford classic is „The Searchers„, at the same time one of John Wayne’s darkest roles. Edwards, a war returnee who shoots wounded men and even corpses, escalates the search for his niece, kidnapped by Indians, to the point of obsession. „The Searchers“ is another frontier fiction in which the ongoing threat to the homesteaders by the displaced Indians serves as the starting point of the story—again with immensely atmospheric shots of Monument Valley, which has long been iconic in the meantime.

-

Major Dundee (1965)

Bildquelle: Columbia

The plot: From a prisoner-of-war camp, Northern Major Dundee recruits a cavalry force with which he invades the interior of Mexico in violation of international law to hunt down marauding Apaches who have just massacred a ranch and an army unit.

A few years before New Hollywood cinema picked up steam, Sam Peckinpah directed superstar Charlton Heston as an ambivalent figure in the mood of New Hollywood—his cavalry officer is an egocentric nonconformist who embarks on a tour de force full of destruction and doom to get his broken career moving forward again. Good and evil cannot be differentiated in this Western.

-

Garden of Evil (1954)

Bildquelle: Twentieth Century-Fox

The plot: Three soldiers of fortune—an ex-sheriff, a card player and a hotshot—are actually on their way to gold-intoxicated California when, during a stopover on the Mexican coast, a woman hires them for a rescue operation for a considerable fee. The journey into the unknown turns out to be a life-threatening adventure due to the presence of Indians.

Henry Hathaway can be seen as something like the topographer of the Western; and in „The Garden of Evil“ he also immerses the scenery in opulent images before which the protagonists pale. Like „The Treasure of the Sierra Madre“ (1948) a few years earlier, the film raises to the fatal gold-digger paranoia and the cynical fate of futile hardships.

-

Valdez is Coming (1971)

Bildquelle: MGM, Norlan Production, Ira Steiner Production

The plot: Mexican Valdez works as a US auxiliary policeman and is humiliated, almost killed, by arms dealer Frank Tanner. The peaceable Valdez, who once raged as a sniper in the Indian wars, mutates into an avenging angel.

When the ex-megastar Burt Lancaster had to realize that he wasn’t bringin in as much money as he used to, he looked for a role for his old age—and found it in experience-saturated Western warhorses who get into sinister constellations. When fellow humanity becomes the discriminated Valdez’s undoing and he nearly croaks in the desert, he becomes a killing machine with the resources of his dark past as an Apache hunter. „Valdez is Coming“ not only takes a pessimistic look at the fragmented society of the Old West, largely indifferent to tyrannical matadors, but is also grippingly staged.

-

Chato’s Land (1972)

Bildquelle: MGM, Michael Winner

The plot: As a „half-breed“ Indian, the innocent Chato is branded a murderer and a posse sets out to hunt him down. On home turf, Chato begins to successively decimate his pursuers, who are armed to the teeth.

As in „Valdez is Coming,“ a minority member is provoked by the majority society—by people who underestimate his true abilities and resources; and in the Western, such a lapse usually ends fatally. The self-righteous Americans invading foreign territory and murdering civilians, that had to (and probably should) be reminiscent of Vietnam.

Charles Bronson with his stoic face and athletic body is an obvious casting, Jack Palance is the hard-boiled leader of the posse. „Chato’s Land“ is about the chauvinistic vigilante zeal of supposedly respectable citizens—whose exodus under the banner of justice becomes a ride to ruin.

-

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962)

Bildquelle: Paramount, John Ford Prod.

The plot: The idealistic lawyer Ransom Stoddard, an unwavering constitutional patriot, has found himself in a Wild West nest, where he tries to defend himself with paragraphs and judgements against the revolver authority of the universally feared Gunslinger Liberty Valance.

„The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance“ features John Wayne in one of his most interesting roles: From the virile local hero who drills the naïve West Coast lawyer (played by James Stewart) in the unwritten laws of the West, cracking whimsical sayings and commanding the atmosphere of every saloon he enters with aplomb, he degenerates over the course of the film into an embittered wreck, smoky and boozy. Stewart, on the other hand, plays an early anti-hero of the Western—through the fate of his character, one learns about the lack of democracy of ordinary people in U.S. democracy and the power of creating legends.

-

The Cowboys (1972)

Bildquelle: Warner Bros., Concourse Prod.

The plot: In the gold rush, rancher Wil Andersen runs out of cattle drivers and hires a dozen teenage greenhorns—more children than adults—for his cattle drive.

The arduous march through „400 miles of the meanest country in the West“ is not only an unconventional coming-of-age trip, but also a small homage by John Wayne to himself—a quarter of a century earlier he led a cattle drive through the prairie in „Red River„, whose overwhelming expanse is captured here by Robert Surtees’ camera. Even the two left-liberals Mark Rydell (director) and Bruce Dern (supporting role) succumbed to the charm of the „Duke“, a political right-winger, on the set.

-

Red River (1948)

Bildquelle: Monterey Prod.

The plot: In his restless daring, cattleman Thomas Dunson sets out with ten thousand head of cattle to march from Texas to Missouri, where he plans to sell his giant herd. Because he acts more and more like a tyrant during the exhausting journey, Dunson’s people mutiny under the aegis of his foster son Matt.

The road trip among westerns: Howard Hawks visualized the endurance strain of a three-month-long cattle drive that finally led over the Chisholm Trail in crazy pictures—a camera spectacle lasting over two hours, the highlight of which is a stampede in which thousands of cattle make their way. In addition to John Wayne, who, contrary to his usual screen image, plays an extremely gloomy figure in parts, the film also features a very young Montgomery Clift, who breathes plenty of life into his fictional character.

-

The Long Riders (1980)

Bildquelle: United Artists, MGM

The plot: The James-Younger gang, led by the charismatic Jesse James, is made up of violence-tested Civil War veterans who continue their guerrilla routine as bank and train robbers after the South surrenders.

Walter Hill’s version of the Jesse James legend belongs to the New Hollywood late harvest and convinces with its realistic scenery and laconic dialogues. As a twist, the film’s cast includes real-life brothers Keach, Quaid, Guest and Carradine.

Hill shows how the faces and bodies of the virile bandits are gruesomely deformed and destroyed as a result of their criminality. Throughout, the final shootout is the anatomy of a brute gunfight and a reinterpretation of 1939’s „Jesse James„ sprinkled with slow-motion sequences in the style of Sam Peckinpah.

-

Day of the Outlaw (1959)

Bildquelle: Security Pictures, MGM

The plot: On the icy frontier of Wyoming a band of soldiers invades a tiny town, fleeing the cavalry with a looted army treasury. A rancher takes them into the snowy mountains, through which he supposedly knows a route, to lure the violence-prone bunch with its dying leader out of town.

As far away as this settler’s nest is from more hostly climes, „Day of the Outlaw“ is far from well-trodden genre paths. The deserters are an unpredictable collection of fortune hunters and psychopaths, their chief an old officer who credits himself with a morality he lost long ago.

André De Toth’s Western runs differently, feels differently and looks differently than most other genre representatives—shot at the end of the fifties, it was ahead of its time.

-

High Plains Drifter (1973)

Bildquelle: Universal Pictures, Malpaso Company

The plot: Concerned small-town residents hire a stranger who is as sure as eggs in a basket when it comes to handling a revolver—he is supposed to protect them from approaching gangsters.

Clint Eatswood’s nameless avenging angel exposes the hypocrisy of capable small-town citizens who, in their desperation, allow him to degrade them. The pointed violence here functions as a symbol for the harshness with which the USA was built.

-

The Shootist (1976)

Bildquelle: Dino De Laurentiis Corp.

The plot: After his cancer diagnosis aged gunslinger J.B. Book retreats with plenty of laudanum to a hotel, which is run by a widow, while profiteers and enemies seek to capitalize on his malaise.

Sometimes fictional and real tragedy interweave in Hollywood cinema, as in „The Shootist,“ John Wayne’s last film before his death from cancer in 1979—the departure of a fictional and real Western legend. The reality of Wayne’s fate gives the film its dramaturgical weight.

-

The Revengers (1972)

Bildquelle: Cinema Center Films, CBS

The plot: Civil War hero and rancher John Benedict wants to hunt down his family’s killers. For his private vendetta he hires a half-dozen outlaws, recruiting them in a Mexican jail.

Certainly not a masterpiece, but not really trash either: „The Revengers“ is a strangely entertaining film, whose charm lies not in its own original achievements, but in a successful arrangement of old familiar things.

It shows how the sheer endless revenge ride morally deforms a once sincere man and at some point degenerates into an aimless end in itself—musically accompanied by Pino Calvi’s concise score, whose electric guitars so nonchalantly break the Western theme.

-

Bad Company (1972)

Bildquelle: Paramount, Jaffilms

The plot: Young Methodist Drew Dixon flees his native Ohio to escape forced recruitment for the Civil War. On his way west, he finds refuge in a gang of young petty criminals who fight their way through the wastelands of the Heartland.

The thoroughly pessimistic mood makes „Bad Company“ an anti-Western that annihilates any outlaw romanticism and portrays the journey through the heart of the USA not as a youth adventure but as an oppressive struggle for survival in a merciless society.

-

Monte Walsh (1970)

Bildquelle: CBS

The plot: Cow hands Monte Walsh and Chet Rollins await the demise of the Old West world they know.

With subtle nuances of their facial expressions, Lee Marvin and Jack Palance succeed in expressing the attitude towards life of an entire social group: the prairie warriors who have struggled all their lives on the cattle trails, but who now threaten to disappear forever in the face of an automobile and mechanized economy. Almost every scene is charged with the inconceivable sentimentality of lost life chances.

-

3:10 to Yuma (1957)

Bildquelle: Columbia Pictures

The plot: Dan Evans is so desperate that the rancher and family man gets involved in a suicide mission: He is to put the notorious, just arrested murderer and gang leader Ben Wade on the train to Yuma, while Wade’s companions are already planning the liberation of their leader.

No western, not even „High Noon„, creates such loneliness in a scenario that is actually loud and bustling, as is typical of the genre, as „3:10 to Yuma„. The bustling Western town of the 1880s is swept clean here, the vastness of the prairie seems claustrophobically oppressive, the sparse use of background music creates an ominous, suspenseful silence. And in the middle of it all, in endlessly excellent close-ups, the confrontation between two men takes place: on the one hand, the outlaw, who hits the neuralgic points of his guard with razor-sharp precision, who on the other hand doesn’t want to look like a coward in front of his two boys in the archaic moral structure of the frontier and wants to provide his troubled wife with an honorable relief in her grueling everyday life with the fee.

„3:10 to Yuma“ is multi-layered: it’s about resisting temptation, acting respectably (both on the side of the lawmen and the bandits), holding one’s own in a fragile world; but much more than that, it’s a wholly unconventional film, a precious genre gem and, with its almost expressionistic atmosphere, simply one of the most cinematographically beautiful Westerns of all time.

-

Terror in a Texas Town (1958)

Bildquelle: Seltzer Films

The plot: An oil-hungry tycoon has a gunslinger, who has long since become anachronistic, kill recalcitrant farmers and ranchers in Texas in order to get his hands on their land. In the Swede George Hansen, who demands justice for his recently murdered father, he finds an indomitable adversary.

Sterling Hayden’s Western protagonist, who doesn’t pick up a revolver once in the entire film and harps on the obligatory showdown on the main street of a small town, inevitably gives „Terror in a Texas Town“ a refreshingly surreal feel.

-

The Ride Back (1957)

Bildquelle: The Associates and Aldrich, MGM

The plot: Sheriff Chris Hamish, who wants to finally get rid of his loser image with a respectable deed, is supposed to bring gunslinger and suspected murderer Bob Kallen from his refuge in Mexico back to the States, where he will be tried.

This Western, quite unusual for its time, lies somewhere between the great Hollywood classics „High Noon“ (1952) and „3:10 to Yuma“ (1957). Much of the New Hollywood era is already present in „The Ride Back„: the dirty realism of sweaty bodies and filthy clothes, slightly surreal strains and characters who are unpredictable in their ambivalence.

-

The Wild Bunch (1969)

Bildquelle: Warner Bros.

The plot: On the eve of World War I, an outlaw gang on the run from bounty hunters heads to Mexico, where they plan to do one last big score under the auspices of a inevitably changing world.

„The Wild Bunch“ is something like the quintessence of Peckinpah cinema—and of the Hollywood Western. In countless details, Sam Peckinpah shows the brutality inherent in human coexistence. His characters are hopelessly lost, whose world inevitably perishes in the face of motorization and urbanization, but who cannot get away from violence as their purpose in life and find in it a strange in-betweenness—and in one of the most brutal, corpse-packed flicks in cinema history, Peckinpah exposes death in the Western for what it is: senseless, cruel and devoid of heroism in a mad showdown.

Text: Robert Lorenz